Program

Call for Session Proposals, Abstracts and Posters

Adaptation Futures 2023 is significant as it is being held for the first time in a hybrid format, potentially including a multi-hub format[1] to acknowledge our responsibility as a climate community to “walk the talk” on climate action. It also seeks to attract more Global South delegates than ever before to the conference and forefront developing country adaptation contexts.

[1]To ensure that this 2023 edition is inclusive, engaging, equitable, and sustainable, McGill’s Faculty of Education and Ouranos are collaborating on a 2-year design-based research project aiming to catalogue lessons on the move to hybrid conferencing from across the academic landscape. For more information about this study, please click here.

Conference Themes

Cutting edge knowledge and experience, of many forms, are needed to drive evidence based decisions for adaptation in the years ahead. The overarching themes of this conference encourage discussion on frontier issues that contain knowledge gaps, transboundary perspectives for adaptation, actionable solutions and connection with development goals.

In all themes there are two cross cutting elements: Integrated systems perspectives, and indigenous knowledges and expertise. Furthermore, all themes relate to larger efforts toward climate resilient development pathways, including enabling conditions needed for climate resilience in diverse contexts. The themes are intentionally phrased to embody cross-sectoral perspectives and to stimulate debate about the progress on the global goal on adaptation. They are relevant to all sectors, e.g., water, food systems, health, the built environment and beyond.

Theme Descriptions

Learning from Indigenous and local peoples’ knowledges and expertise in adaptation

Indigenous Peoples have been stewards of lands, waters and oceans for generations anticipating and responding to climate variability and change.

There is increasing recognition of the value of community expertise, plurality of knowledges, including Indigenous Knowledges (IK) and Local Knowledges (LK) for informed climate resilience pathways. IK & LK’s have value for framing adaptation across genders and generations of society quite apart from its place-based local practices.

There is a growing consensus among climate scholars and practitioners that climate adaptation strategies and policies should use the best available knowledge, with exchange and interaction between IK / LK and Western knowledge. Dialogue between a range of knowledge-holders offers opportunities for effective and context-specific climate adaptation planning and through integration of these discourses for transformational adaptation.

Some of the emerging issues include:

- Ways in which Indigenous ways of learning and communication including storytelling and experience in sustainable natural resources and biodiversity management serve as foundations for effective climate adaptation.

- Examples of the integration of IK and LK in the discourse of climate change, policy formulation and implementation: opportunities and challenges.

- Examples of IK & LK being mainstreamed into adaptation planning and action as a climate justice issue.

- Cases where the underpinnings of Indigenous worldviews can provide new insights for adaptation and challenge dominant modes of practice.

Dealing with multiple risks: Compound, cascading, cross-border climate change risks

Climate change risks result from dynamic interactions between climate-related hazards, exposures, responses, and vulnerabilities of affected human or ecological systems.

There is growing appreciation of the complexity of interactions among multiple drivers of climate change risk and vulnerabilities. The IPCC projects every region of the world will increasingly experience concurrent and multiple changes in climate hazards with every further increment of global warming. Much attention has been paid to understanding compound (or extreme) climate events.

However, we know very little about how to respond to these compound climate events. Further, we know very little about how two or more drivers of intersectional vulnerability, exposure or response compound with each other (e.g., gender and migrant status) nor how their compounding interactions affect other multivariate drivers of climate change risk in ways that make risks more or less severe.

Clarity is needed regarding the interactions that generate risk that are affected by responses to climate change. We particularly need to avoid where responses increase vulnerability and may lead to maladaptation. There is also growing concern over the unpredictability and severity of impacts arising from cascading and compounding effects of these interactions and when risks cascade across economic, political, ecological and biophysical systems to affect climate change risk. A deep appreciation of the spatial and temporal complexity of compounding and cascading climate change risk, and the implications for adaptation planning is, however, in its infancy. Effort is needed to track and understand the ways in which risks interact across sectoral and regional boundaries, and at different points within food and other socio-ecological systems (from production to consumption). New methods are needed to link physical and socio-economic drivers of complex climate change risks and vulnerabilities, including for futures-oriented research, practice and policy development.

Issues arising:

- Examples of the ways in which climate change risk assessment can account for multiple interactions between the many drivers of climate change risk over spatial and temporal scales? How can these assessment support better and more systemic actions?

- Identifying the most important drivers of climate change risk across many contexts

- Examples of how understanding multiple drivers of exposures, hazards, vulnerabilities and responses, and their interactions, can inform climate risk management and avoid maladaptation?

- What do climate services and tools look like when we accept that risk and the required climate actions are compound and complex?

- How do non-climate factors (such as human conflict or COVID19) interact with climate change and other risks to affect climate change risks and vulnerabilities and the required climate actions?

- How can understanding of compound risks and vulnerabilities inform new approaches to transformative futures research and practices?

Making adaptation choices: managing trade-offs and seeking effective adaptation

AR6 highlights the need for a robust evidence-based framework to support adaptation choices, reduce maladaptation and enable more effective risk management.

An integrated framework for adaptation feasibility was used across the AR6 report. It takes a systems perspective and considers the interconnections, synergies and tradeoffs of adaptation across different dimensions – social, economic, institutional, technological, environmental, and geophysical; synthesizing existing barriers to adaptation that supports human well being, food security and livelihood security in the near term.

This framework is quite recent (used for the first time in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on 1.5 °C global warming) and also has some knowledge gaps.

Some emerging learning questions that can be further documented relate to its:

- Sharing best practices and lessons learned about effective adaptation practices and policy responses

- How to operationalize adaptation and resilience in the global goals?

- What are the current methods to track and measure adaptation effectiveness, adequacy and progress? Pitfalls and opportunities in tracking adaptation effectiveness?

- How to incentivize anticipatory adaptation?

- How do these metrics capture change over time, both in risks and adaptation outcomes, and for whom? How do they inform the need for changes in adaptation action?

- How do we understand and assess effectiveness and adequacy, and pursue it through policy and practice, when the goalposts of what is adequate and effective are changing?

- Given different values attached to systems-at-risk, how do feasibility/effectiveness frameworks create space for capturing the interactions between adaptation options?

- How can big data and artificial intelligence better support effective responses to climate risks?

- What is needed from the adaptation community in terms of contributions towards the global stocktake?

- How can we better understand and address maladaptation as it happens?

When we can no longer adapt

There is greater recognition that adaptation (and mitigation) efforts will not be sufficient to prevent all complex climate risks and vulnerabilities.

Therefore, climate change, through hazards, exposure and vulnerability generates impacts and risks that can surpass limits to adaptation and result in increasing losses and damages. The literature shows that many human and natural systems are already near or beyond their soft adaptation limits, leading to the increased likelihood of damages and losses. In some places and for certain systems, we are approaching hard limits to adaptation (e.g. coral reefs, extreme heat in South Asia by 2050). In such challenging contexts, achieving the objectives of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) requires a careful design of flexible Climate Resilient Development Pathways (CRDPs) that take into account climate change adaptation and mitigation in a sustainability context.

Scientific debates around limits to adaptation calls for transformational adaptation and mitigation to reduce risks. Such a systems perspective indicates that risks and resulting vulnerabilities will become more complex, and adaptation will become more challenging in some regions, including Africa, the Arctic and Small Islands. Limits to adaptation will be more pronounced, and damages and losses more substantial. While the concept of limits to adaptation is increasingly used in adaptation literature, there are still some critical gaps, and useful lessons to learn.

- Some adaptation limits have been identified (e.g., ecological systems), but little is known about limits in social systems – what drives limits in these systems? where these might lie, who might they affect and how? and what are the practical consequences of reaching such limits?

- How can we understand limits to adaptation vis a vis mitigation and the changing goalposts of climate change and climate risks?

- How and for whom adaptation is constrained and limited, and how policy and practice can factor this knowledge in to create more equitable and sustainable climate action for all?

- Influences of social-institutional contexts and economic organization on the limits to adaptation

- Planned relocation is being considered where limits to adaptation are reached, what lessons can be learned from other fields, such as the impacts of relation from large scale dam development over many decades and relocations as a result of other environmental or social concerns? What happens to voluntarily immobile populations?

- Example of metrics for tracking losses and damages under high and low adaptation and mitigation scenarios.

Who wins, who loses, who decides: Equity & justice in adaptation

The impacts of climate change are disproportionately experienced by marginalized and vulnerable groups.

Efforts to support adaptation must therefore grapple with profound questions of ethics, equity and justice. Adaptation efforts offer an opportunity to support transformations toward more equitable and climate-resilient societies. To realize this promise, however, adaptation efforts must tackle the systems that perpetuate inequalities on the basis of identity. Multiple and intersecting categories of identity, including, but not limited to gender, sexuality, age, class, race, caste, ethnicity, indigeneity, citizenship status, religion, and (dis)ability affect how different people experience the risks and impacts of climate change and natural hazards, and benefit (or not) from interventions intended to enhance climate adaptation and resilience. Taking an intersectional approach is necessary, but the conceptual and practical approaches to achieving this require further development.

There has been a proliferation of interest in ‘climate justice’ in recent years, across the spectrum of academia, civil society, business and government. Addressing climate change as a question of justice, however, is challenging and the mechanisms for doing so are weakly developed. Many types of justice are critical to engage with in a changing climate, including procedural justice (who is included in decision making and who is left out?), distributive justice (who gains and who bears the costs?), recognitional justice (who is counted as vulnerable and who is left out?) and epistemic justice (whose knowledge counts when decisions are made?), among others.

Examples of issues emerging:

- Examples of justice and equity being integrated (or not) into planned relocation related to climate change, responses to displacement and support to migrants in sending and receiving areas?

- In what ways do our climate assessments and adaptation plans and actions meaningfully consider climate equity & justice?

- Best practices to safeguard, protect and promote Indigenous peoples’ rights, including treaties and legally binding decisions on land management, through adaptation efforts?

- How do efforts to pursue loss and damage support more just adaptation efforts, and vice versa?

- What methods are proving effective in breaking down the hierarchy of knowledge systems in adaptation and creating an even playing field for Indigenous and local communities?

- Sharing climate-just futures, and methods for how can these be envisioned and achieved;

- Do we risk increasing inequities as we adapt? Can we monitor, avoid, and anticipate this?

- Examples where adaptation finance is offered and administered in ways that promote equity and justice in the context of climate change?

- To what extent can taking a wellbeing perspective to adaptation planning and implementation address justice and equity adaptation concerns?

The power of nature for climate action

Human and natural systems are deeply connected.

While the role of nature in mitigating climate change (through for example carbon sequestration) is well understood, more effort is needed to fully unpack the climate-nature nexus, and to understand the opportunities and risks to harness the power of nature to support adaptation to climate change and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Approaches such as nature-based solutions (NbS) and ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) have some limits, and garnered increased interest and scrutiny. The growing interest in NbS and EbA has offered the promise of marrying climate change responses, the conservation and management of ecosystems and biodiversity, and Indigenous and local peoples’ land stewardship practices. However, these approaches have also raised questions and concerns, especially among researchers in the global South, about the implications of these approaches in local contexts and the trade-offs between groups and across scales.

Some topics arising:

- Best practice examples where NbS and EbA reduce risk and vulnerability to climate change, including a consideration of the trade-offs across scales and between groups in society

- Interrogating the role of biodiversity security and management within NbS, and how they complement each other

- Lessons learned about the combinations of nature-based, infrastructural and behavioral adaptations that are effective in the short, medium and long term in different contexts

- Suites of adaptation options that work best in different social-ecological contexts, toward different kinds of outcomes, and the synergies and trade-offs with mitigation and sustainable development

- Impacts of NbS and EbA on socio-economic processes, from an intersectional perspective;

- How approaches at the nature-climate nexus can be decolonised and avoid the perpetuation of colonization that could result from climate action

- Looking beyond NbS and EbA, toward a focus on lessons learned from Indigenous land management

Teaching and learning adaptation in a changing climate

Are our education systems up to the task of teaching and supporting effective learning about adaptation now that we have passed 1.1C global average warming and climate change is already a reality for many?

What would need to change in order to get this right, and where do we find exceptional examples of effective teaching and learning? Educators and learners alike face a number of challenges in the decades ahead. A challenge, and a key opportunity, is finding ways to accommodate ontological pluralism inside and outside of classrooms. For example, identifying pedagogical methods that offer equal footing to Indigenous and scientific knowledge, especially in place-based adaptation efforts.

Another challenge is actively supporting learners through multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinary learning pathways. This is critical, but many systemic barriers and institutional inertia within university systems, and Western science more generally, make it challenging. For example, these learning pathways require breaking down the traditional barriers between social science, natural science, law and other faculties, enabling students to move between faculties during the course of their studies. This is seldom an option in Universities. Finally, a clear challenge for anyone teaching on adaptation is how to ensure that students do not experience new knowledge as a driver of eco/climate anxiety. Teaching needs to inspire hope while also balancing the realities of the climate crisis.

Some topics arising:

- Canadian Indigenous scholars have pioneered Two-Eyed Seeing as a pathway toward holistic thinking, ontological pluralism and epistemic justice: what has been learned about teaching and learning through this approach, and what lessons are there from around the world with similar efforts?

- Adaptation in the Anthropocene will require climate change professionals capable of dealing with highly complex decision making environments, often under deep uncertainty – how are secondary schools and tertiary education institutions rising to this challenge?

- Examples of adaptation skills such as climate knowledge brokering, storytelling and communications that might need to be taught in the Anthropocene?

- What competencies, mindsets, or orientations are needed to teach for uncertain, unknowable futures amidst the accelerating impacts of the climate crisis?

- What models of institutional transformation can inspire us?

- Engaging with grief and hope in the teaching and learning of the climate crisis. Is a case study model the only/best approach? Students seem to seek ‘success’ stories as well to balance out the doom. How can serious games and fiction play a role in teaching in the Anthropocene?

Inclusive adaptation governance and finance: how do we get there?

Suitable governance mechanisms, effective and inclusive decision-making processes, an enabling institutional context and finance are critical for implementing, accelerating and sustaining climate responses and Climate Resilient Development.

These include political commitment, institutional frameworks, development-focused policy environments with clear goals and priorities, enhanced knowledge on loss and damage, limits and solutions, access to adequate financial resources, the means to ensure such finance reaches the local level and inclusive and cross-sector decision making processes. Governance efforts that advance climate resilient development goals account for the dynamic, uncertain and context-specific nature of climate-related risk, and its interconnections with non-climate risks, and recognise that local agency and greater mobility is essential to building adaptive capacity.

Despite the renewed commitments to climate policy objectives through the Paris Agreement in recent years, there are still major governance barriers that hinder climate resilient development. Finance for adaptation also remains inadequate. Governance and adaptation finance barriers include, among others, slow policy implementation progress, incoherent and fragmented climate governance approaches and climate agendas both within and across countries, inadequate, inflexible and inappropriate finance mechanisms and financial flows to those who need it, poor stakeholder engagement in policy planning, deep inequalities and asymmetric power relations exacerbating challenges and the vulnerability of marginalized groups, particularly in low income regions with lower governance capacity.

Some topics arising:

- Making climate governance be more inclusive – participation of marginalised groups in policy processes to enable transformational responses to climate change

- Best case examples of development policy to recognizing trans-local livelihoods, and how policy can support multiple forms of human mobility as an adaptation strategy

- Lessons learned about governance and/or finance mechanisms for climate smart agriculture at scale

- Examples of equitable finance that ensures local climate action happens in a manner that communities have an active voice in determining their finance needs

- Examples of innovative financial solutions at community level that can be scaled out

- Examples of capacity development and learning practices to stimulate sustained institutional change under deep uncertainty

- Role and contribution of Indigenous Peoples customary institutions and self-governance system as foundation for climate change adaptation.

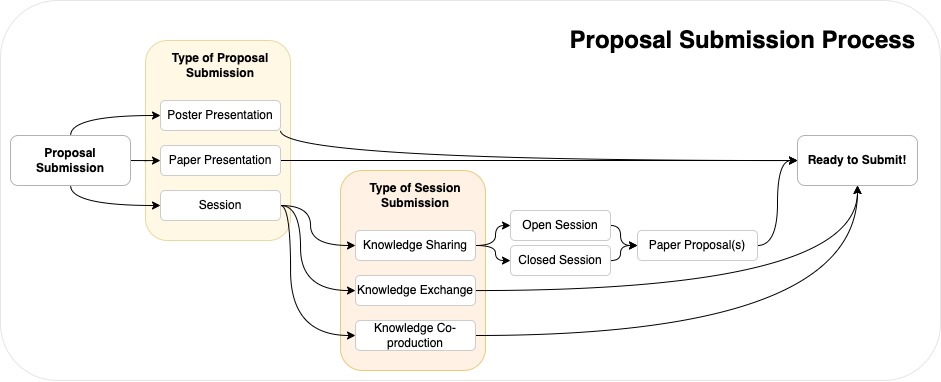

PROPOSAL SUBMISSION

We value diversity and inclusivity so the conference would like to invite submissions from a large range of specialists: climate change adaptation researchers, practitioners, early career researchers, community representatives, policymakers, industry representatives, etc. As indicated below, you can choose to submit a virtual poster presentation, a paper presentation or a session.

To promote equity and broader participation in Adaptation Futures 2023 (AF2023), an individual can only serve as a lead author for one Paper/Poster Presentation Proposal and one Session Proposal.

A. Proposal for Traditional Paper and Poster Presentations

– Virtual Poster Presentation: Posters combine a visual summary of the findings of a paper/study with the opportunity for individualized and informal discussion of the presenter’s work. Online presenters will be offered asynchronous sessions with e-poster and/or video as your presentation. Please be noted that no synchronous presentations will take place, as they will be available during the entire conference period. Submissions for poster sessions include an abstract of up to 300 words. Submission Requirements: Introduction, objectives, method, findings, significance of the work for policy and practice.

– Traditional Paper Presentation: The proposals for traditional paper presentations are submitted by individuals (with one or more authors). They are reviewed based on rigor and contribution to scholarship and/or practice. At AF2023, the paper presentations are formed into a thematic session by conference organizers. Submissions for a traditional paper presentation include an abstract of up to 800 words. Submission Requirements: Introduction, objectives, method, findings, significance of the work for policy and practice.

B. Proposal for Sessions

To promote knowledge exchange and co-learning for actionable solutions, we encourage other submission formats other than traditional paper and poster presentations. Three types of sessions will be offered at the Adaptation Futures 2023 conference:

1. Knowledge sharing sessions (‘one way’): To disseminate information through a one-way process of sharing knowledge. These sessions are presentation-based to translate and communicate knowledge and ideas that help people make sense of and apply information.

2. Knowledge exchange sessions (‘two way’): To disseminate information through a two-way process of sharing knowledge. These sessions are discussion-based to focus on translate and communicate knowledge and ideas that help people make sense of and apply information; To facilitate informal dialogues, collective learning, and innovation for system-level change.

3. Knowledge co-production sessions (building new knowledge together): To improve knowledge use in decision-making through more of a two-way process; To engage in negotiating, networking, collaborating and managing relationships and processes; To foster action and change through a co-production approach to making use of the existing stock of knowledge.

Submissions for a session include a proposal of up to 500 words (summary, description of session format, and anticipated outcomes). Session organizers will also be asked how their session takes into account the gender, equity, and social inclusion considerations. Please note that reviewers may suggest organizers to change the types of sessions proposed, based on what they deem appropriate for the proposal at hand.

Knowledge sharing session proposal can be submitted as either an open or closed session.

– Open Sessions: The session organizers define the topic and format of the session and invite one or more presenters to moderate/chair the session. The conference Scientific Committee will select the contributors to the session from the pool of submitted ‘Paper Presentation’ abstracts. All contributions for an open session will need to be submitted via the conference abstract submission process.

– Closed Sessions: The session organisers define the topic and format of the session, and invites all speakers/contributors in the session. Closed sessions therefore require the session proposal to include details of all the speakers/contributors and include the abstract of the included paper presentations. See template above for additional details.

Given that there is no ‘Paper Presentation’ abstracts associated with Knowledge exchange and Knowledge co-production sessions, the option between open or closed is not applicable.

Session will be 90 minutes long.

Indicative examples of session formats are included in the PDF version of this call.

SELECTION PROCESS AND CRITERIA

OUR MAIN CRITERIA FOR SELECTION WILL BE QUALITY, RELEVANCE, DIVERSITY AND INCLUSIVITY. WE PARTICULARLY WELCOME SESSIONS THAT:

– Consider gender, equity, accessibility, and social inclusion concerns

– Facilitate dialogue between research and government, practitioners, civil society, private sector, international organizations and foundations

– Contribute to a diverse and balanced program that focuses on solutions and innovations

– Consider the inclusion of Indigenous and local knowledge in adaptation processes

– Make adaptation a core element of sustainable development, investment and planning.

– Contribute to a conference program with a wide range of topics, stakeholders, scales and regions

– Showcase examples (case studies, tools, good practices and why they matter, etc.) or research that are internationally applicable

– Involve a partner organization from two or more different countries, organizations or adaptation community

SUBMISSION GUIDELINES

All submissions must be submitted in accordance with the guidelines below:

– Submissions must be completed by January 30, 2023.

– All abstracts must be submitted through the online form.

– Abstracts may be submitted in English or French. The submission must be made in the language of presentation at the conference.

– Submitter must be the lead presenter of the abstract or chair of the session.

– Abstracts must follow the official template in Word format, per submission type (see Abstract Templates above).

– Submissions must be in Arial font, size 11.

– Submissions may include up to 1 image or table (maximum 10MB).

– Please only use standard abbreviations or define them in full.

– Accuracy is the responsibility of the author. Abstracts will be published as submitted. Please ensure that all abstracts are carefully proofread before upload.

FUNDING OPTIONS

Limited financial support grants will be available, but we cannot give any guarantee at this stage. Please do not submit a proposal if you are not prepared to register to the conference.

CONTACT

AF2023 Secretariat – JPdL International

1555 Peel Street, Suite 500 | Montreal QC H3A 3L8 | Canada

Tel: +1 514 287-9898 Ext. 222 | Fax: +1 514 287-1248

af2023@jpdl.com

adaptationfutures.com

Twitter: @AdaptFutures23